When I first read Patrick Leigh Fermor’s trilogy of European travel memoirs – A Time of Gifts, Between the Woods and the Water, and The Broken Road – I had never been east of Colorado. I had twice when I was in high school gone on weeklong backpacking treks, one in the Uinta mountains and another in the canyons near Escalante. Yet those had been with the Boy Scouts, whereas PLF’s walk from the Hook of Holland to Constantinople was carried out alone. Before I encountered Fermor, I harbored nothing more than a base-level Romanticized image of traveling solo through a foreign country, a composite that was 70% informed by Ethan Hawke in Before Sunrise while the remaining 30%, which replaced Ethan Hawke’s 1995 goatee, was derived from Lord Byron. I was immensely lucky to read Fermor’s trilogy before coming to Japan by myself a few short months later. He renovated my Hollywood expectations — for travel, for a foreign solitude, for learning a culture à l'improviste — all of it, 100% — into something far more subtle.

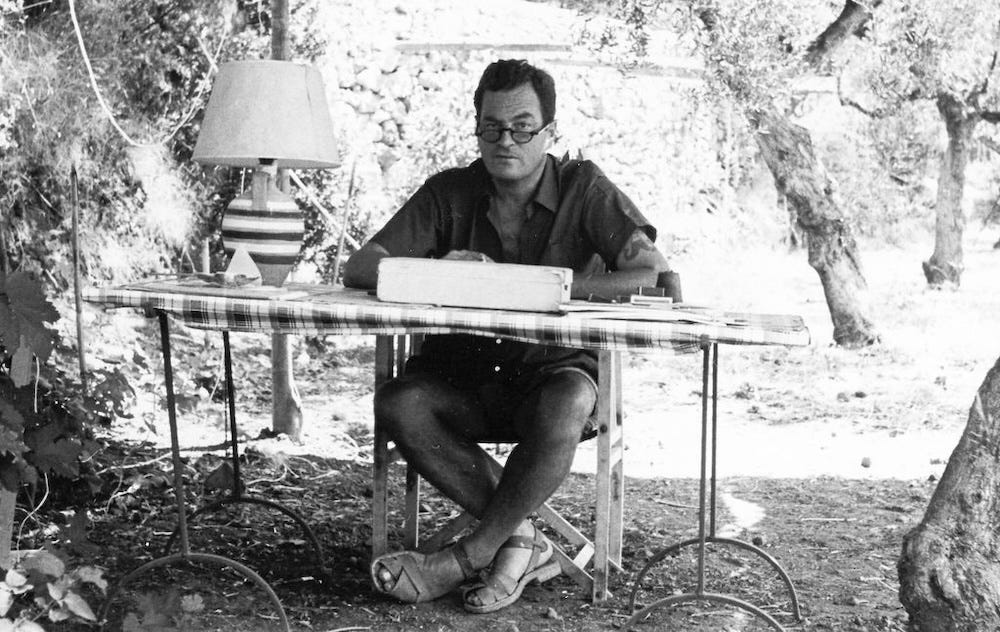

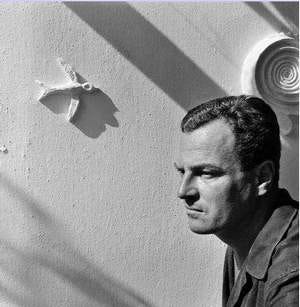

Patrick Leigh Fermor was born in London in 1915. He was a self-reported difficult child, albeit the kind of difficult child who trades Shakespeare quotations with his mother, and was enrolled in several “alternative” schools before a final expulsion from The King’s School in Canterbury for one count of holding hands with a local girl. The last report his mother received from the school before his expulsion had described him as “a dangerous mix of sophistication and recklessness.”1 The newly-liberated Fermor, coming to the apparently reasonable conclusion that a standard life in British society simply wasn’t his lot, went to London to become a writer. There he proceeded to write nothing, party wildly, and, by consequence, run out of money. At the age of 18 he got the idea for a trip from the Hook of Holland through to Constantinople, one that would show him all the parts of Europe which would have been most strange and exciting to a young man in 1933: Germany, Prague, Romania, Hungary. “I would travel on foot,” he later recounted of his travel plan, “sleep in hayricks in summer, shelter in barns when it was raining or snowing and only consort with peasants and tramps.” He hoped that by the time he got to Turkey he would finally have worked through his inability to focus and be able to write something worthwhile.

The three books that recount this odyssey are indeed worthwhile. His prose style and painterly sense of place harmonize such that they become indistinguishable. A Fermor sentence is very often, and very fittingly, like a road in that it begins in one place and, taking whatever curves, digressions, or scenic byways it might, ends in another. It replicates the depth and interwovenness of Eastern European culture and history as well as Fermor’s descent into that depth, his wandering along that interweaving. His is a Europe of hard political boundaries but soft cultural ones, a Europe made up of far more dialects and architectures than its nations can account for, a Europe with prodigals and prodigies flowing thick as the Rhine. At every turn of his journey PLF finds premonitions of the Byzantine capital ahead, signs of sultans and Islam and of a people as ancient as the Roman Empire. And the road behind is never really past as tips and facts from friends parted with miles before prop up the lone traveler’s body and mind. Following PLF, one comes to the awareness that his steps are awakening the crisscrossed echoes of the thousands and thousands of lives that have traveled these ways before.

Fermor’s story also flows in adventurous currents. At times it can resemble a classic, homey fantasy tale, something in the vein of The Hobbit. Like when, for example, the young traveler heads for a famed beer hall and finds himself squeezing between great specimens of German corpulence, men with faces so beer-blushed and round they look like babies. Or when a barkeep introduces him to Himbeergeist, a raspberry schnapps which diffuses in the drinker all the warmth and good feeling of ambrosia. Fermor possessed a rare unity, something essential for any good travel writer, which is a sense for magic which can flow direct and unexaggerated from his real-life exploits into the written work. Where Tolkien invents The Prancing Pony, Fermor revives his beer halls and pubs. They are equally good places to be.

There are several images from the trilogy which have stayed with me since reading it for the first time, any of which should serve, even if I can only offer a degraded recreation,2 as sufficient reason for anyone to read the books that house them.

Take, for example, this description of an unusual vehicle on the Dutch canals in winter:

“It was an ice-yacht — a raft on four rubber-tyred wheels under a taut triangle of sail and manned by three reckless boys. It travelled literally with the speed of the wind while one of them hauled on the sail and another steered with a bar. The third flung all his weight on a brake like a shark’s jawbone that sent showers of fragments flying. It screamed past with an uproar of shouts as the teeth bit the ice and a noise like the rending of a hundred calico shirts which multiplied to a thousand as the raft made a sharp right-angle turn into a branch canal.”

Or the interior design of a German bourgeois:

“Except for the panorama of the lights of Stuttgart through the plate glass, the house was hideous — prosperous, brand new, shiny, and dispiriting. Pale woods and plastics were juggled together with stale and pretentious vorticism, and the chairs resembled satin boxing-gloves and nickel plumbing. Carved dwarves with red noses stoppered all the bottles on the oval bar and glass ballerinas pirouetted on ashtrays of agate that rose from the beige carpets on chromium stalks.”

But most persistent in my memory is a scene from The Broken Road where Fermor finds himself stranded on a Grecian beach at night in the rain, facing such darkness that he cannot safely continue in any direction. For a few excruciating hours Fermor makes slow, groping progress along the bay, visions of a rising tide like a death sentence in the black midnight. Salvation comes in the form of a band of fishermen, found drinking ouzo around a fire in a cave, who take in Fermor for the night and treat him to a show of Greek full-heartedness. A cave is a cave, of course, and it is furnished as you might expect a fishermen’s cave to be, but in Fermor’s telling it may as well be Ali Baba’s hideout. Warm firelight dances on the walls and ceiling as his feelings of dread burn away, and the scene climaxes with one of the hosts performing an ecstatic folk dance. As the dance accelerates and the fisherman’s jumps and swings become more powerful, the table on which their drinks are set is cleared away — so that he may grab it with his teeth, and, barrel-neck bulging, include it as the final, dramatic display of a in this nightmare-turned-revery.

As one can tell from the quotations above, Fermor’s writing is often at or near the high watermark of vivid prose, and he does occasionally dye a page purple. Most writing about Europe in the 1930’s was under the minimalist influence of Hemingway, Camus, and Malraux, with pens across the continent drilling deeper and deeper inside the individual’s psyche. The at times courtly prose and objective focus with which Fermor paints his travels is a welcome contrast with other records of the time period. One is glad to see German cathedrals and Hungarian castles given the color they deserve.

Another contrast with the era’s canonized: the political tone of Fermor’s trilogy, if there is even one to speak of, is an aftershade of pink, an embarrassed flush that shows in reminiscences on the Socialist Utopianism of British intellectuals in the 1930’s.3 Being a traveler, Fermor took in Europe one eyeful at a time, and the trilogy is an attempt to set down those eyefuls, in their discord as well as their continuity, as best as he can. He offers no synthesis where he saw none, and he sketches no conflicts he himself was not privy to. And if inclusion of old-fashioned adjective and metaphor give color to his work, the lack of any long-winded theorizing helps seal it.

The reason why this style was necessary for Fermor is not that it could serve his nostalgia; the quaint wood-and-brick villages he passes through on his way between the Capitals of Culture, as well as the providential aristocratic connections which time and again lend a hand during his penniless trek, will for the most part be wiped out in the coming years of termoil. Fermor wrote about his experiences decades after the fact, having deployed with British forces in Greece during World War II.4 There is a sadness to the trilogy which rises up from the crevice between the main text, where a village Such-and-such or a Duke So-and-so are named, and the footnotes, where Fermor reports that Such-and-such has been closed behind the Iron Curtain, that So-and-so was sent to a death camp. The crevice widens as Fermor heads deeper into Europe; the final volume is titled The Broken Road. This gap gives the work a sense of shadow most travel literature doesn’t attempt. Like that other maverick of modern style, Proust, he reaches across time to perform an act of literary resurrection — an effort which may be what makes these three books a masterpiece trilogy.

In Japan, I have found myself a happy, if admittedly half-rate,5 PLF imitator. The Fermor Solo Travel Method is superior. It consists in walking wherever you can; foregoing fine dining in lieu of cheaper, heartier fare; trusting locals over guidebooks but yourself over locals; taking the time to silently think through the many aspects — natural and human — of the space you have traveled through that day; and keeping yourself open to both the road behind and the road ahead. Fermor’s way of traveling was distinct from vacationing. In imitating him I have found his style of movement yields a partly academic, partly spiritual experience. It is, admittedly, not very restful, though it does yield a deep sleep at the end of the day.

Allow me to compare this approach to the general mindset of travelers in 2024. Japan is probably the number-one travel destination in the world at the moment. A weak yen and the desire for Instagram posts about Shibuya Crossing and Mount Fuji are at the source of this popularity. Having lived here for over a year now I’ve come to realize that what most international tourists get out of Japan is, from the Japanese point of view, a kind of recital, a not entirely inauthentic experience but a sanitized one. This is in part because what the average consumer truly wants out of a trip to Japan is to board a flight so long it might as well be a portal to another world, and to arrive in that other world and watch it play out for them like a film while they enjoy a break from the tormented politics at home by escaping to a country which does have an otherworldly capacity for ignoring its own politics. Many of the tourists I’ve met here have told me the same thing: “It’s so peaceful.” What they mean is: “as a tourist, I don’t have to worry about my wallet being stolen.” It’s a funny misphrase. Willfully enchanted by a sugary-mystic Japan they seem to forget that they are also in one of the most stress-plagued countries in the world, where many people begin working their health into the ground at some point in the seventh grade just to prop up a faustian economy.

The tourist’s view of Japan — the clean, polite, well-mannered utopia of liberalism — is rather bland, as most otherworlds turn out to be. It lacks a real heart. It is the necessary product of a way of traveling which prioritizes unreal photographs over real people. Before I read Fermor, when I had my Ethan Hawke/Lord Byron vision of travel, what I really wanted were some nice photos and a few idiosyncratic souvenirs and one or two Very Inspiring Poetic Moments.6 Contemporary life pays tribute to the idea of travel but shrouds it in solipsism, in tour guides and reservations and three-day-two-night itineraries which in the final analysis look something like an old-fashioned diving suit, a clumsy assemblage made to protect the individual from their environment. Fermor’s writing and his style of travel is not, perhaps, a conscious reaction against this view — it is too subtle to be that — but it is an alternative. He is never about pure consumption, never about finding the supreme experience for the individual. Fermor’s project is more about giving one’s curiosity and conversation to a foreign place and people, and then letting be.7 How different from the attitude of the average international traveler is this confession: “ever since I could remember, my boredom threshold had been so high that it scarcely existed at all.”

The great benefit of the Fermor Method is access to a pure vein of the wonder replicated in his trilogy. If one can get the trick of walking as he did, then the landscapes deepen and shade, and — what is even more precious to me — they become populated. It is hard to imagine that without the influence of Patrick Leigh Fermor I would have ever struck up a conversation with the middle-aged woman next to me at a Hiroshima Carp game or accepted a stranger’s lift up to the base of the Zao-San trail. As a benefit of the former, I earned initiation into the well-coordinated world of Japanese baseball cheers, which really does require fan-to-fan transmission.8 From the latter I took, in addition to a perfectly pleasant ride that wound up salvaging the day, the best burger I’ve eaten in Japan, served at the stranger’s off-season ski lodge before I played piano for the staff and resident dog. These are only two examples of many memorable interactions in a notoriously shy and high-strung country; they are more clear to me than any photo I’ve taken here. The Fermor trilogy has turned out to be something like an inoculation; before the self-centeredness of modern travel habits could make me suffer, it showed me how traveling solo need not mean traveling alone. If, boots de-soled and head split with hangover, an 18-year-old Brit with little German and less Romanian could be so moved by his chance encounters in beer halls, caves, and monasteries — what excuse have I?

An epithet I find endlessly funny. Whatever schoolmaster wrote it clearly spent a good deal of time wondering how exactly to describe the young PLF, and in this case it is probably fair to assume that only deep, deep hatred could motivate the don in question to come up with such precise words. Yet for all that it also happens to sound like something M would say about James Bond (incidentally, a character which Fermor was compared with in his BBC obituary).

The obvious and ideal method here is, of course, to quote from these scenes, which is what I have done in the case of A Time of Gifts because it is one of the few English books I brought with me to Japan. The other two volumes are separated from me by a Pacific Ocean and then some. This is an impediment to quotation. There may be other errors regarding my recollection of Between the Woods and the Water and The Broken Road, since I do not have them to hand.

A whole chapter of A Time of Gifts is set aside for Fermor’s observations on German fascism. However, the observations as well as the criticism appending them, are primarily concerned with the fanaticism of individual Germans, the explanations for Hitler’s rise given by Nazis as well as opposing citizens, and the sight of propaganda and brownshirts. This is travel memoir, not Eichmann in Jerusalem.

Equally famous to his writing is the part he played in the capture of the Nazi general Heinrich Kreipe.

The first tour style trip I took through the cities of Shikoku led me to discover a distaste for cheap hostels, especially at the height of summer, and I have since opted for equally unglamorous but superiorly air-conditioned business hotels since.

Rest assured I’ve found all of these in spades; one finds them coming regardless of travel style.

Quote from one of Fermor’s lovers in an LRB review of The Broken Road: “‘Most men are just take, take, take. With Paddy it’s give, give, give.’”

In Japan on business, I used to sneak away when I could (not easy, as I’m sure you know), and walk, sometimes just taking the subway to another neighbourhood and walking around for a while and eating in some casual restaurants, a good strategy for Tokyo (and horrified my Japanese work mates when they found out). It was glorious in Kyoto especially—never would have gotten as good a sense of it any other way. . . And, btw, it was a joy in Greece, in his footsteps in the Mani the tough part he loved. Thanks for the memories!

I'm visiting Japan next year, the last thing I want is Piccadilly Circus or Leicester Square (I say this as a Londoner), so will take a metro to the last stop on the line, eat and walk about, maybe a beer, sketch a bit.

Also, I'm lucky enough to have a Japanese pal in Tokyo, he knows what I like.

If you like PLF then you'll dig Freya Stark.